KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Companies that sell consumer health tech aren’t overseen by any federal agency or law. They are relatively free to collect, use, and even sell user health information.

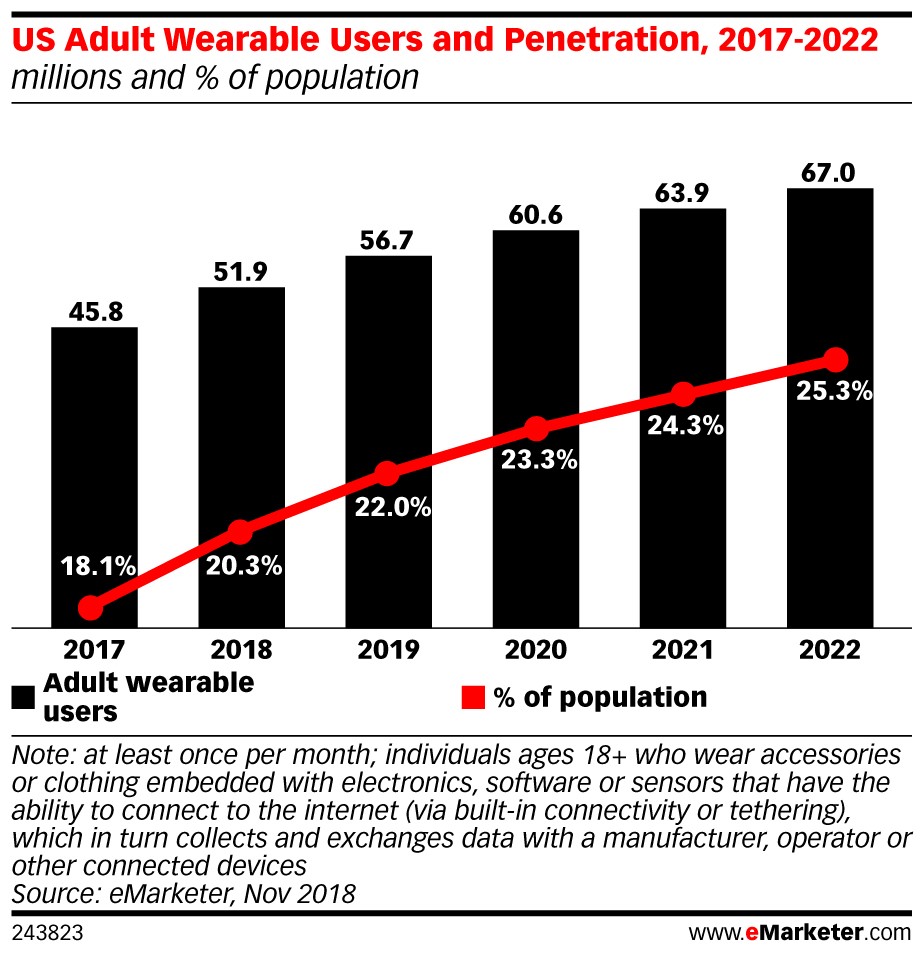

- About a quarter of U.S. adults (56.7 million people) are using wearable devices, many of which collect highly sensitive health data. Outside of health care, these technologies aren’t subject to HIPAA privacy and security standards.

- Tens of thousands of people buy direct-to-consumer DNA kits every year. Genetic testing companies sometimes sell users’ genetic data to third parties, such as pharmaceutical companies.

- Genealogy databases have become a more powerful resource to identify individuals than law enforcement databases. Some DNA databases, like GEDmatch, are open to the public.

- The newly introduced Protecting Personal Health Data Act would extend privacy regulations similar to HIPAA to consumer health apps, wearables, and direct-to-consumer genetic tests.

We use our biology to identify ourselves all the time. Your smartphone facial recognition or fingerprint sensor uses your biometric data. The fitness tracker on your wrist collects your heart rate and steps.

But, as health apps, wearable health tech, and DNA kits become ingrained in the American consumer’s life, it’s becoming clear that the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) doesn’t account for the unprecedented amount of health data consumers share with companies.

The Gap Between HIPAA and the Consumer Health Tech Market

HIPAA was designed to keep patients’ protected health information (PHI) private and secure in the context of a healthcare organization – a provider, clearinghouse, or health plan – that provides service to patients. The HIPAA Privacy Rule limits how and when an organization can use or disclose PHI and established strong standards for de-identifying PHI. The Security Rule established safeguards to keep electronic data secure. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provides oversight to make sure healthcare organizations comply with HIPAA.

However, businesses that sell products and services outside of health care aren’t kept to the same privacy and security standards. There is no federal oversight on how these companies collect, use, or disclose consumers’ health data. This gap in how health information is treated should give us pause to reconsider the role of federal privacy and security regulations in the consumer market.

This article will look at the privacy issues with health apps, wearable tech, and genetic testing, as well as the proposed Protecting Personal Health Data Act that seeks to fill the gap left by HIPAA.

Health Apps and Wearable Tech: Does HIPAA Apply?

In 2019, about a quarter of U.S. adults (56.7 million people) will use a wearable device every month. Though some wearables don’t collect health data, many devices do, including Fitbit, Apple Watch, and other activity trackers.

Wearables can track many aspects of your health, from heart rate to sleep patterns to glucose levels. According to a Scripps Translational Science Institute study, wearables are more effective in studying certain health conditions than traditional testing, allowing a provider to remotely track a patient’s health 24/7.

Though a piece of health data alone, like heart rate, would not be considered PHI under HIPAA, keep in mind that most health tracking apps and wearables connect health data with your identity. If a provider asks a patient to submit health data from their app or device for the purpose of health care, HIPAA protects the data as PHI. In fact, patient-generated health data are becoming a major part of patients’ health records.

However, according to MicroMD, “If a consumer is using a wearable to collect health data for their own personal use, HIPAA doesn’t apply.” One report found that, of 43 fitness apps, 40% collected high-risk data, such as the user’s full name, financial information, health information, location, date of birth, and more.

Though some of the major tech companies, like Samsung and Apple, claim to support HIPAA compliance, in the consumer health market, user data aren’t protected with the level of security required by federal law. Unfortunately, this means companies can – and do – share and sell user data to third parties according to their terms and conditions.

An opinion piece from The Hill noted that “consumers today seem to be more interested in the health benefits of wearable devices, rather than privacy.” If consumers don’t care, is health information privacy a problem or a personal choice? Should tech companies that provide consumer health products be regulated with the same strictness as the healthcare industry?

Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing: An Identity Crisis

Direct-to-consumer genetic tests have also taken the world by storm – genetic testing companies are expected to make $10 billion in sales within a decade.

Genetic testing services, like MyHeritage, 23andMe, and Ancestry, can identify 700,000 genetic markers, allowing them to pinpoint relatives, physical characteristics, and health factors. According to the privacy statement on Ancestry.com:

“Your DNA Data is also used to provide other information about you, such as your connection to genetic relatives in our database and any genetic markers associated with physical traits, such as hair color or traits associated with your health and wellness.”

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing services have become more powerful at identifying people – even people who are not themselves in genealogy databases – than current law enforcement databases. Law enforcement can’t search a DNA database, like Ancestry, unless they have a warrant.

However, genetic testing companies can release information into public databases, like GEDmatch, where law enforcement (and anyone else, for that matter) can use the DNA to locate people of interest. In fact, an estimated 60% of European Americans can be identified by genetic relatives through direct-to-consumer genetic testing services. To test the precision of using DNA databases to locate people, both an MIT scientist and Harvard Medical School professor used “anonymous” genetic samples from a public research database and found they could successfully identify individuals.

Consider, also, that anyone who has previously consented to have their DNA used in research cannot withdraw it. And – regardless of consent – genetic testing companies sometimes sell users’ information to third parties for research.

This is a big privacy concern. These services fly in the face of HIPAA and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, both of which protect DNA from unauthorized or harmful use. Again, there is a gap between federal privacy regulations and the less-than-private practices that happen in the consumer market.

This makes us wonder: is HIPAA’s reach too short? Should federal law extend to businesses that provide consumer health tech and services?

Extending the Reach of HIPAA – in a Sense

Recognizing that HIPAA is insufficient to cover emerging health technologies, senators Amy Klobuchar and Lisa Murkowski recently introduced a privacy bill to fill the gaps in the federal HIPAA law. The Protecting Personal Health Data Act seeks to extend regulatory protections to consumer health apps, wearables, and direct-to-consumer genetic tests to give consumers the same protection both inside and outside of HIPAA.

Within six months of enactment, the bill would require the secretary of HHS, the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, the National Coordinator, and others to “promulgate regulations to help strengthen privacy and security protections for consumers’ personal health data that is collected, processed, analyzed, or used by consumer devices, services, applications, and software” -Sec. 4(a).

Our policies must evolve to keep up with advancements in recent technology. By enacting important modern protections for consumers’ personal health data, our bipartisan legislation puts the privacy of American consumers first. pic.twitter.com/iVoMXjjkVC

— Sen. Lisa Murkowski (@lisamurkowski) June 14, 2019

The federal task force would:

- Develop protections based on the sensitivity of different types of health information collected by or contained in consumer products

- Develop standards for getting user consent regarding their health information and have clear and appropriate means of obtaining consent (rather than simply presenting terms and conditions) and withdrawing consent

- Limit how much information is transferred to third parties

- Provide a way for users to access a record of the health data companies have collected, analyzed, used, and disclosed, as well as a way to delete or amend personal information

- Study the effectiveness of current de-identification methods for genetic and biometric data

- Evaluate security standards, such as encryption and transfer protocols, for wearables, health apps, and software

- Develop resources to educate and advise consumers of genetic testing about the risks, benefits, and limitations of these services

The priorities outlined in the Protecting Personal Health Data Act parallel some of the privacy and security protections of HIPAA. According to a press release from Sen. Klobuchar’s site:

“New technologies have made it easier for people to monitor their own health, but health tracking apps and home DNA testing kits have also given companies access to personal, private data with limited oversight,” Klobuchar said. “This legislation will protect consumers’ personal health data by requiring that regulations be issued by the federal agencies that have the expertise to keep up with advances in technology.”

However, many are concerned that the expanded reach of health data regulations will discourage entrepreneurs from entering the healthcare industry or advancing health technology. McAfee senior vice president and chief technology officer Steve Grobman said that lawmakers are walking a tight line: too many regulations might limit innovation or “keep medical professionals from doing their job” (The Hill).

What do you think? Should consumer health tech companies be subject to federal legislation to protect consumers’ health data? Are privacy and security standards similar to HIPAA even necessary outside of a healthcare setting?

Share your thoughts with us on Twitter @hipaatrek.

Are you up to date with HIPAA?

Check out our cheat sheet for staying up to date with changing regulations!